Caregivers (CGs), as well as the person receiving care, often want the care receiver to be able to stay at home for as long as possible. Although this situation can place various burdens on CGs and the care receiver, it also has social and, in particular, health economic advantages (Wübker et al., 2015). Many different factors contribute to the “success” of a home care situation.

One such factor of considerable importance is a good relationship between CGs and care receiver. Scientific findings show that a good relationship reduces the likelihood of the person being cared for moving from their home into a retirement or nursing home (Spruytte et al., 2001). In addition, a good relationship is associated with a lower perceived caregiver burden (see also the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers, Long and Short Versions), more positive aspects of the home care situation (see also the Benefits of Being a Caregiver Scale), and lower levels of depression among family CGs (Lum et al., 2014; Tanji et al., 2008).

The aim of the new assessment of the quality of the relationship between CGs and the care receiver was to:

- present the construct to be measured in an easy-to-understand form (result: use of visual imagery),

- to keep it as concise as possible (result: only 1 item), in order to

- achieve a high level of acceptance for a topic that is sometimes taboo (relationship quality).

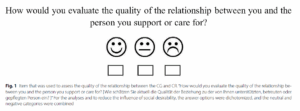

The result of this development process is the evaluation of relationship quality using a smiley scale with three possible responses:

The item on the quality of the relationship between CGs and the care receiver was validated using a sample of 962 CGs with an average age of 62 (75.6% women).

Validity was tested and confirmed on the basis of four hypotheses (H1 – H4):

- H1: The relationship quality is negatively associated with perceived subjective caregiver burden (measured by the BSFC-s (Graessel et al., 2014)).

- H2: The relationship quality is positively associated with perceived positive aspects of the care situation (measured with the German Version of the “Positive Aspects of Caregiving Scale”; Tarlow et al., 2004).

- H3: The relationship quality is positively associated with intrinsic care motivation.

- H4: The relationship quality is negatively associated with extrinsic care motivation.

Results:

The response regarding relationship quality was negatively correlated with subjective caregiver burden and extrinsic caregiving motivation; that is, a positive assessment of relationship quality (the “smiling smiley” was checked) was significantly correlated with a lower subjective caregiver burden and significantly less often with extrinsic caregiving motivation. A positive correlation was found with the perceived positive aspects of the caregiving situation and intrinsic caregiving motivation; that is, a positive assessment of relationship quality (the “smiling smiley” was checked) was significantly correlated with more perceived positive aspects of the caregiving situation and significantly more often with intrinsic caregiving motivation.

Thus, all four hypotheses regarding the validity of the classification of the quality of the relationship between CGs and the care receiver at home could be confirmed. Further details can be found in Becker et al. (2024).

Checking the smiling smiley indicates a rather positive relationship quality, checking the neutral smiley is interpreted as a neutral relationship quality, while checking the sad smiley indicates a rather negative relationship quality.

Note: In scientific evaluations (analysis of sample results), it may be useful to combine the “neutral smiley” and the “sad smiley” into one category: “rather negative relationship quality.” This combining minimizes the effect of social desirability (reluctance to admit a “negative” relationship quality and instead preferring to indicate the “neutral smiley”). This leaves two evaluation categories: “rather positive relationship quality” (the “smiling smiley” was checked) versus “rather negative relationship quality” (the “neutral smiley” or the “sad smiley” were checked).

Becker, L., Graessel, E., & Pendergrass, A. (2024). Predictors of the quality of the relationship between informal caregiver and care recipient in informal caregiving of older people: presentation and evaluation of a new item. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 342.

Graessel, E., Berth, H., Lichte, T. & Grau, H. (2014). Subjective caregiver burden: validity of the 10-item short version of the Burden Scale for Family Caregivers BSFC-s. BMC Geriatrics, 14, 1-9.

Lum, H. D., Lo, D., Hooker, S., & Bekelman, D. B. (2014). Caregiving in heart failure: relationship quality is associated with caregiver benefit finding and caregiver burden. Heart & Lung, 43(4), 306-310.

Spruytte, N., Van Audenhove, C., & Lammertyn, F. (2001). Predictors of institutionalization of cognitively‐impaired elderly cared for by their relatives. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(12), 1119-1128.

Tanji, H., Anderson, K. E., Gruber‐Baldini, A. L., Fishman, P. S., Reich, S. G., Weiner, W. J., & Shulman, L. M. (2008). Mutuality of the marital relationship in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 23(13), 1843-1849.

Tarlow, B. J., Wisniewski, S. R., Belle, S. H., Rubert, M., Ory, M. G., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2004). Positive aspects of caregiving: Contributions of the REACH project to the development of new measures for Alzheimer’s caregiving. Research on Aging, 26(4), 429-453.

Wübker, A., Zwakhalen, S. M., Challis, D., Suhonen, R., Karlsson, S., Zabalegui, A., … & Sauerland, D. (2015). Costs of care for people with dementia just before and after nursing home placement: primary data from eight European countries. The European Journal of Health Economics, 16(7), 689-707.

You can register to download the scales here.

! Those responsile for this website guarantee that all information provided during registration will be treated confidentially, in particular that it will not be passed on to third parties.

Downloading is permitted for non-commercial use only, which means specifically that

- the respondent completing the self-assessment tool incurs no immediate (direct) costs (billing as a health insurance benefit by third parties, e.g., doctors, is possible) and

- the Relationship Quality is not resold to third parties in any form as part of a combined survey tool consisting of several survey instruments (e.g., as part of a larger, fee-based assessment tool).

Caregiver (CG)